Introduction

Some of the most popular posts at Kung Fu Tea have examined vintage images of traditional martial artists. These are also among my favorites to research. Yet it seems that I have neglected this subject with all of the other projects that have come up this summer. Hopefully this post will go some distance towards rectifying that oversight.

The internet is both a blessing and curse to those doing research. It allows us to regularly discover new treasures. Yet such finds are often presented in a decontextualized way that makes interpreting them challenging.

This post adds two new vintage images to our discussion. Unfortunately both are “orphaned,” meaning that I have yet to locate the exact place and date of their creation. Nor do they share a single medium. Nevertheless, these images are thematically linked in ways that suggest an interesting moment in the evolution of Western views of Chinese boxing.

Two Images, One Theme

Our first image is a late 19th century albumen print showing four martial artists. I have not been able to locate any information about the photographer who produced it. The dress and hair styles of the athletes suggest that it cannot have been taken later than 1911. The fact that this is almost certainly an albumen photo (note the sepia tones and the ease with which the corner of the thin photographic paper bent off its backing) suggest a date prior to 1900, at the latest. Thus this photograph dates to somewhere from 1860 to 1900.

Perhaps, if we allow ourselves to indulge in a little speculation, it might be possible to shave a few decades of this interval. The fact that this was shot in a photography studio against a backdrop suggests the need for a longer exposure time. Consider also the subject matter and composition of this image.

The mirrored symmetry in the shot is remarkable. Three of the individuals are shirtless, revealing highly muscled bodies. The two boxers in white stand at ease, meanwhile the inner pair appear to be wrestling.

At first it appears that the theme of the photograph might be something like “physical strength through struggle.” No one would doubt the athletic ability of these individuals.

This point is further emphasized by the heavy stone weights (commonly used by wrestlers, boxers and soldiers) that define the physical space on which the camera focuses. Given the faded nature of the photo it is hard to make out any details of the ball in the foreground, but I suspect that upon closer inspection we would discover that it is carved from stone as well.

But brute strength is not the only idea that this shot is meant to evoke. While the inner pair is involved in combat, the boxers on the outside stand at ease. The photographer also chose a painted backdrop meant to evoke the bucolic Chinese countryside of rivers, mountains and quaint cottages. Given the importance of Willow Ware in creating the romanticized early 19th century Western mental image of Chinese life, such an artistic choice is unlikely to have been unintentional.

The symbolic nature of the composition is further confirmed by two seemingly out of place artifacts in the foreground. Here the viewer finds a tea pot and cup. Of course China was famous for its tea exports. Interestingly both tea and China serving ware were among the few export items that could be found in pretty much any middle class house in the West. They were both ubiquitous and evocative of material comfort and success. China provided the indispensable goods that for many people symbolized a “civilized” life.

At first glance we might assume that the intended subject of this image is the traditional martial arts. Yet upon further meditation I suspect that this is not really the case. Instead the photographer has taken China writ large as his subject. It is in the juxtaposition of the heavy training weights and the delicate teapots, or the violent wrestlers and the peaceful countryside, that the true intent of the image appears.

What at first appeared to be a simple symmetry is really a sort of visual dialectic. This is not so much “China” as any visitor would visually see it on the street. Rather, the composition of the various elements suggests that this may have been an attempt to communicate the nature of China as the photographer had experienced it. Or perhaps it might be more accurate to say as the viewer wished to understand it. In its mix and juxtaposition of symbols the image resembles the still life paintings of a previous era.

Given the wonderfully evocative nature of this photograph it’s a shame that I have not been able to figure out who produced it. Yet rest assured, the search continues.

While thinking about my frustration in researching the first image, I was reminded of another piece of hand combat related art that has also been on my mind. A few years ago I first encountered an engraving by the French artist Felix Elie Regamey titled “La Preparation Aux Examens Militaires, A Canton.”

It’s a great image, and at the time I had very much wanted to add it to my collection. Yet as I researched it I quickly discovered that compared to his better known Japanese subjects, Regamey’s Chinese works do not seem to have received very much attention. In fact, it is hard to know exactly when this piece of art was first done (engravings, by their very nature, lend themselves to reproduction and subsequent republication throughout an artist’s career.)

Later in his life Regamey adopted a more relaxed style which, to my untrained eye, looks as though it may have been influenced by Japanese or Chinese brush paintings and wood block prints. He does seem to have produced other Chinese subjects in the more structured and formal style seen above between roughly the middle of the 1860s and the middle of the 1880s. It seems likely that this particular study also dates to the same basic time period.

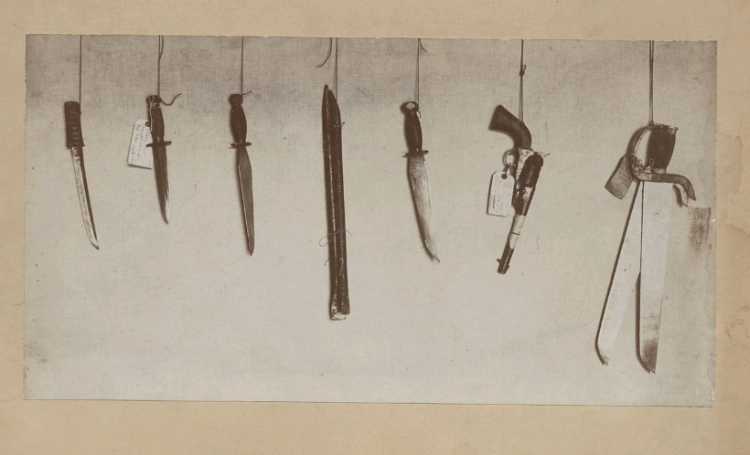

Again, the dominant theme of the image is physical strength. Here we see two martial artists preparing for the military service exam by lifting the sorts of heavy stone weights used in the testing of candidates. Around them are the other implements used in the exam.

On the left wall we see a rack of the heavy knives, or halberds, that one was expected to wield. On the other side of the image hangs archery equipment, perhaps the most critical aspect of the exam. All that is missing is a horse, as candidates were also expected to know how to ride. The two martial artists are at the same time highly muscled yet relaxed.

Once again, it is impossible to miss the unique mirrored symmetry of this scene. The only item that is out of place is the stone block that is currently being used. The natural result of this composition is to focus the viewer’s attention on the only singular item in the image, the religious altar placed in the center of the composition. Here we see the expected lamps, incense and offering table. Yet as the eye expands outward we quickly encounter something else, calligraphy.

By this the viewer learns that these exam candidates are not mere day laborers or common soldiers. Rather they are educated individuals, masters of both the body and the mind. Of course basic literacy skills were necessary to complete the military exam, yet one did not have to be a trained scholar to do well.

The important thing in this case is not how accurately this image captured the actual level of literacy possessed by the average examination candidate. More critical is what it communicated to its Western viewers about the nature of Chinese life and society.

A dialectic logic again emerges from the composition. The overriding impression is of a balance between physical strength and cultural attainment. The “mysterious orient” is shown as existing in that liminal joining of the body and the mind. Of course such suggestions would have resonated with the romantic turn in late 19th century European thought.

Yet in some respects this engraving is more complicated than the photograph. Boxing and wrestling were popular 19th century pastimes in both the East and West. Athletics never really needed any justification for a Western consumer. A fast paced wrestling match was a good in and of itself. The virtue bestowed by success in such a realm was self-evident to all.

In contrast, the individuals in the second image are not really “athletes.” They are aspiring military officers. And Western viewers surely would have noted that they were training with the bow well into the age of the rifle and revolver. While a generally positive image, and one that noted the physical strength and dedication of the Chinese people (e.g., it is an image of daily physical training, and not the exam itself), this picture also would have underlined China’s militarily backwardness.

If the audience is meant to approach this piece from a more “romantic” perspective, an emphasis on physical effort rather than mass produced industrial goods is not necessarily a bad thing. Yet while the overall aesthetic of the first photograph is rather “modern,” (wrestling was just as popular in 1900 as it had been in 1800) there can be no doubt that the second image plays into widespread notions of the “timeless and inscrutable orient.”

Chinese Boxers before the “Sick Man of Asia”

A number of Chinese and Western commentators in the early 20th century went out of their way to paint Chinese individuals as physically weak, often unhealthy, individuals. Many of China’s economic, social and political struggles were laid unfairly at the feet of its citizens. This tendency reached its zenith in the early 20th century when long running debates about the effects of opium use and a string of military defeats coalesced in a (mostly domestic) debate as to whether, and why, China was the “Sick Man of East Asia.”

I have discussed these developments in other posts. One should not underestimate how important these debates were in shaping the TCMA in the modern era. After the humiliating setback suffered during the Boxer Rebellion (when the martial arts were very nearly driven out of the social discourse), these discussions opened a space in which martial artists could claim to advance the national good through a return to traditional values.

The impact of these discussions can still be felt today. The mythology of the Jingwu Association, as well as Bruce Lee’s films, ensures that these images (and insecurities) live on.

What interests me about both of these images is that they predate this entire social discourse. I suspect (admittedly with insufficient evidence) that both the engraving and the photo date to roughly the early 1880s. But even if that estimate is off by a decade in either direction, they are clearly a product of the period of China’s “Self-Strengthening Movement.”

The enthusiasm and self-confidence in these images is palpable. They neither doubt the physical capabilities of the Chinese people, nor do they seek to turn away from core cultural values in the quest for athletic excellence (as recommended by the May 4th reformers). Nor are they shy about communicating this self-confidence to the world.

In terms of geo-political events, the 1880s came a generation after China’s defeats by the British in the South, and 15 years before its diplomatically devastating loss to the Japanese. While China clashed with France in the middle of the 1880s, it managed to win a number of battles and avoided the same sense of military humiliation. The production of such images even suggests some sort of market for visions of a stable and strengthening China in the West. Meanwhile, the Self-Strengthening Movement was giving rise to diverse efforts, some of which contributed to the rise of modern Taijiquan as well as other martial arts. Yet all of this would be abandoned following the national defeats suffered in 1895 and 1900.

Eventually the fierce public debate over China’s status as the “Sick Man of East Asia” would subside, and a growing sense of cultural confidence would again characterize the traditional martial arts. Still, images from an earlier era force us to ask how the evolution of these fighting systems would have unfolded in the absence of the Sino-Japanese War and the waves of revolution, political chaos and cultural self-doubt that followed in its wake. Both images offer us a glimpse into this realm of alternate possibilities.

oOo

If you enjoyed this discussion you might also want to read: Two Encounters with Bruce Lee: Finding Reality in the Life of the Little Dragon

oOo